Why I Finally Embraced MLflow 2.0 for Production Pipelines

I still have nightmares about a specific deployment from three years ago. It was a Friday afternoon (classic mistake), and I was trying to push a Scikit-Learn model to production. The training script lived in a Jupyter notebook named final_v3_really_final.ipynb, the hyperparameters were scribbled on a sticky note, and the environment requirements were… well, “it works on my machine.”

When the model hit the staging server, it crashed immediately. Version mismatch. We spent the entire weekend reverse-engineering the specific combination of library versions and data preprocessing steps that created the artifact. That weekend was the catalyst for me taking MLOps seriously.

Fast forward to late 2025, and the ecosystem looks entirely different. While I’ve experimented with everything from Weights & Biases News to Comet ML News, I keep coming back to the structure provided by MLflow 2.0 and its subsequent updates. It’s not just about logging metrics anymore; it’s about enforcing a rigid, reproducible standard on the chaos of machine learning development. If you are still running loose scripts and hoping for the best, you are doing it wrong.

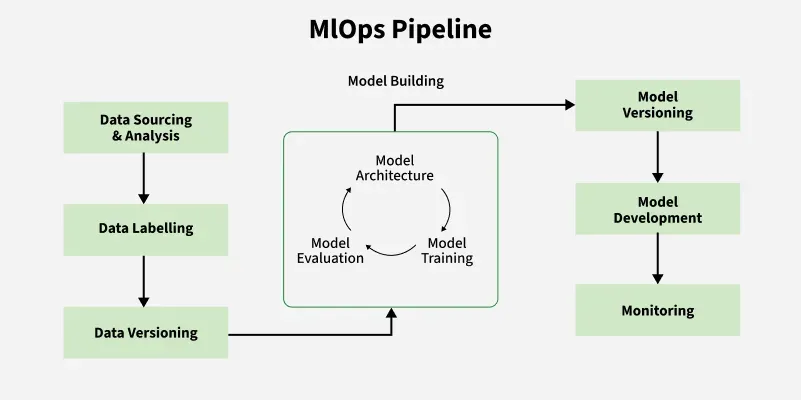

The Shift from Logging to Lifecycle Management

In the early days (MLflow 1.x), I treated the tool purely as a digital notebook. I’d sprinkle mlflow.log_param() and mlflow.log_metric() throughout my messy code. It was better than nothing, but it didn’t solve the structural problem. I could still log garbage.

The real power of the 2.0 era—and what I rely on heavily now—is the concept of MLflow Recipes (formerly Pipelines). This opinionated structure forces you to separate your data ingestion, splitting, transform, training, and evaluation steps into distinct, cacheable modules. When I first tried to port my spaghetti code into a Recipe, I hated it. It felt restrictive. But once I got used to it, the speed gains were undeniable.

Here is what a typical configuration looks like in my current setup. Instead of hardcoding paths, I drive everything through a YAML configuration that MLflow reads to orchestrate the run:

recipe: "regression/v1"

target_col: "fare_amount"

primary_metric: "root_mean_squared_error"

steps:

ingest: {{

"using": "parquet",

"location": "./data/taxi_data.parquet"

}}

split:

split_ratios: [0.75, 0.125, 0.125]

transform:

transformer_method: "fit_transform"

train:

estimator_method: "encapsulated_model"

evaluate:

validation_criteria:

- metric: root_mean_squared_error

threshold: 5.0This YAML file drives the execution. If I change the training logic but not the data processing, MLflow knows to reuse the cached result of the ingest and split steps. This caching mechanism alone saves me hours of compute time every week, especially when working with larger datasets typical in Apache Spark MLlib News contexts.

Taming the LLM Wild West

The biggest shift in my workflow over the last year involves Generative AI. The industry pivot to Large Language Models (LLMs) broke a lot of traditional MLOps tools. You can’t just log “accuracy” for a chatbot. This is where the recent MLflow News updates regarding the LLM evaluation API have saved my sanity.

I manage several RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) pipelines. Initially, I tried building custom evaluation harnesses using LangChain News and LlamaIndex News, but maintaining the evaluation logic was a nightmare. MLflow’s integration allows me to log the model, the prompt, and the retrieval context in one go.

I specifically use the mlflow.evaluate() API with custom metrics. I don’t just trust the default metrics; I define specific criteria for “hallucination” and “toxicity” using a judge-model approach (often GPT-4 or a local Llama 3 variant). Here is how I set up an evaluation run for a RAG system:

import mlflow

import pandas as pd

from mlflow.metrics.genai import evaluation_example, make_genai_metric

# Define a custom metric for answer relevance using a judge model

relevance_metric = make_genai_metric(

name="relevance",

definition="Relevance measures how well the answer addresses the user's question.",

grading_prompt="Score the relevance from 1-5. 1 is irrelevant, 5 is perfect.",

examples=[evaluation_example(input="What is MLflow?", output="It is a tool.", score=2, justification="Too vague.")],

model="openai:/gpt-4",

parameters={"temperature": 0.0},

aggregations=["mean", "variance"],

greater_is_better=True,

)

# My evaluation dataset

eval_df = pd.DataFrame({

"inputs": ["How do I deploy a model?", "Explain MLflow Recipes"],

"ground_truth": ["Use the model registry...", "Recipes provide structure..."]

})

with mlflow.start_run():

results = mlflow.evaluate(

model="runs:/some_run_id/model",

data=eval_df,

targets="ground_truth",

model_type="question-answering",

extra_metrics=[relevance_metric]

)

print(f"Mean Relevance: {results.metrics['mean_relevance']}")This snippet handles the complex logic of calling out to an external LLM to grade my model’s performance. It integrates perfectly with OpenAI News or even Anthropic News providers. Before this, I was manually inspecting CSV files of chat logs. Never again.

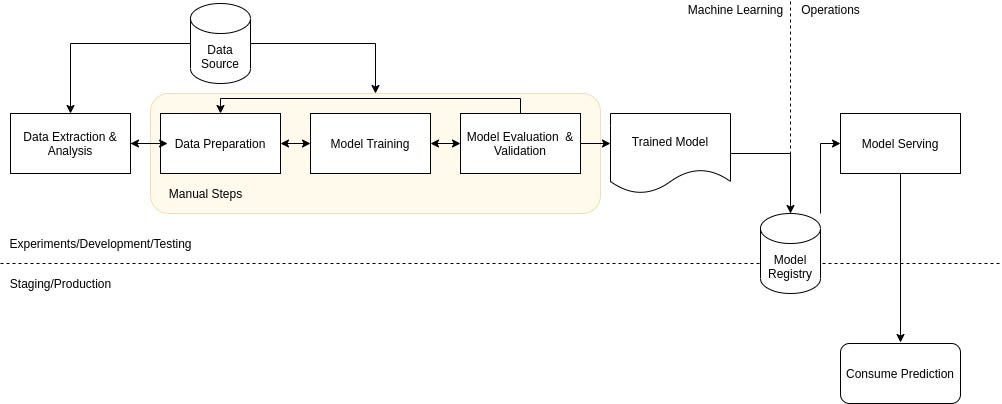

The Model Registry as a Gatekeeper

Another area where I’ve become militant is the Model Registry. In the past, “deployment” meant copying a pickle file to an S3 bucket. Now, I refuse to deploy anything that hasn’t passed through the Registry’s stage transitions.

The “Deployment Client” features allow me to create aliases. Instead of tracking version numbers like v1, v2, or v354, I use aliases like @champion and @challenger. My inference services (running on Kaggle News kernels for testing or AWS SageMaker News for production) are configured to pull the model tagged @champion.

This decoupling is critical. I can update the model behind the @champion alias without restarting the inference server or changing the application code. It separates the data science lifecycle from the software engineering lifecycle.

Here is a simplified workflow I use to promote a model programmatically, ensuring no manual clicking in the UI is required:

from mlflow import MlflowClient

client = MlflowClient()

model_name = "customer_churn_predictor"

# Find the best run from the latest experiment

best_run = client.search_runs(

experiment_ids=["123"],

order_by=["metrics.accuracy DESC"],

max_results=1

)[0]

# Register the model

result = client.create_model_version(

name=model_name,

source=best_run.info.artifact_uri + "/model",

run_id=best_run.info.run_id

)

# Assign the alias - this is the atomic switch

client.set_registered_model_alias(

name=model_name,

alias="champion",

version=result.version

)

print(f"Version {result.version} is now the Champion.")This script runs inside my CI/CD pipeline (usually GitHub Actions). If the tests pass, the alias moves. If not, the production system stays on the old version. It’s boring, reliable, and exactly what I need.

Integration Challenges: It’s Not All Smooth Sailing

I won’t pretend MLflow 2.0 is perfect. My main gripe is still the setup complexity when dealing with distributed training. When I scale out using Ray News clusters or DeepSpeed News configurations, the logging can sometimes get fragmented if the worker nodes aren’t authenticated correctly against the tracking server.

I spent three days last month debugging an issue where my PyTorch News Lightning trainer was logging metrics from rank 0 correctly, but artifacts from rank 1 were vanishing. The solution involved a custom callback ensuring that only the main process talks to MLflow, but the documentation on this specific edge case was sparse.

Furthermore, while the UI has improved, it can get sluggish when you have experiments with thousands of runs. I often find myself using the API to fetch data and visualize it in a local Streamlit app instead of relying on the native dashboard. It’s a workaround, but one I’m willing to accept for the backend reliability.

The Competition: Why I Stick with MLflow

I often get asked why I don’t use Weights & Biases News exclusively. Don’t get me wrong, W&B has a superior visualization layer. Their charts are beautiful, and the collaborative reports are top-tier. However, MLflow wins for me on the deployment end. The way it packages dependencies (Conda, Docker, Pip requirements) alongside the model artifact is more robust for the “Ops” part of MLOps.

Tools like ClearML News and DataRobot News offer compelling all-in-one platforms, but they often require buying into their entire ecosystem. MLflow is open enough that I can swap out my training infrastructure (maybe moving from Google Colab News to RunPod News) without having to rewrite my tracking logic. That portability is my insurance policy against vendor lock-in.

Looking Ahead to 2026

As we close out 2025, the boundaries between “traditional” ML and GenAI are blurring. My pipelines now mix XGBoost classifiers with LLM-based summarizers. MLflow 2.0 handles this hybrid complexity better than anything else I’ve tried.

If you are looking to modernize your stack, don’t just upgrade the package version. Adopt the philosophy. Move to Recipes, enforce strict registry gates, and automate your evaluation. It takes effort to migrate, but the peace of mind on Friday afternoons is worth every second of refactoring.