Engineering the Future of Bio-AI: Building Scalable Infrastructure for AlphaFold-Era Discoveries with Go

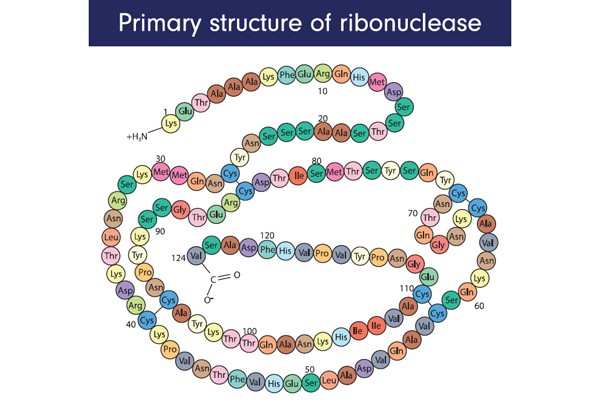

The landscape of artificial intelligence is undergoing a seismic shift, moving beyond text generation into the realm of physical sciences. With the latest Google DeepMind News highlighting the arrival of AlphaFold 3, the industry is witnessing a revolution in predicting protein structures and molecular interactions with atomic precision. This breakthrough is not merely a scientific curiosity; it is a catalyst for accelerating drug discovery and understanding the fundamental machinery of life. While the core modeling of such systems often relies on Python-heavy frameworks like JAX or PyTorch, the infrastructure required to scale these predictions to an industrial level demands a different set of tools.

For systems engineers and ML operations (MLOps) specialists, the challenge shifts from model architecture to system architecture. How do we handle millions of inference requests? How do we preprocess terabytes of Protein Data Bank (PDB) files concurrently? This is where the Go programming language (Golang) shines. Known for its simplicity and robust concurrency model, Go is becoming the backbone for deploying heavy AI workloads.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore how to build high-performance data pipelines suitable for the AlphaFold era. We will bridge the gap between scientific breakthroughs and production engineering, utilizing Go’s goroutines, channels, and interfaces to manage the complexity of modern AI systems. Along the way, we will touch upon the broader ecosystem, including NVIDIA AI News regarding hardware acceleration and Vertex AI News for managed deployments.

Section 1: Modeling Biological Complexity with Go Interfaces

The foundation of any AI application is data representation. In the context of Google DeepMind News regarding molecular biology, we deal with heterogeneous entities: proteins, DNA, RNA, and small molecule ligands. To build a system that prepares data for a model like AlphaFold, we need a flexible type system. While dynamic languages handle this loosely, Go’s strict typing combined with interfaces offers a way to enforce structure while maintaining flexibility.

When ingesting data for training or inference, we often need to treat different molecular structures uniformly. For instance, whether we are processing a protein chain or a ligand, both have atomic mass, coordinates, and binding potential. By defining a Biomolecule interface, we can create a polymorphic system that processes these entities without caring about their underlying implementation details.

This approach is critical when integrating with vector databases—a hot topic in Pinecone News and Milvus News—where structural embeddings need to be stored efficiently. Below is an example of how to structure this domain logic in Go using interfaces.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

// Coordinate represents a point in 3D space (Atomic position)

type Coordinate struct {

X, Y, Z float64

}

// Biomolecule defines the behavior required for any molecular input

// destined for the AI inference pipeline.

type Biomolecule interface {

GetID() string

CalculateMass() float64

ExtractFeatures() []float64 // Simulates feature extraction for ML

}

// Protein represents a protein chain structure.

type Protein struct {

ID string

Sequence string

ResidueCount int

AtomicWeights []float64

}

func (p Protein) GetID() string {

return p.ID

}

func (p Protein) CalculateMass() float64 {

var total float64

for _, w := range p.AtomicWeights {

total += w

}

return total

}

// Simulates generating embeddings or features for a model like AlphaFold

func (p Protein) ExtractFeatures() []float64 {

// In a real scenario, this would involve complex tensor math

// potentially calling out to C libraries or ONNX Runtime.

features := make([]float64, len(p.Sequence))

for i := range p.Sequence {

features[i] = float64(p.Sequence[i]) / 255.0

}

return features

}

// Ligand represents a small molecule drug candidate.

type Ligand struct {

ID string

SMILES string // Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System

AtomCount int

}

func (l Ligand) GetID() string {

return l.ID

}

func (l Ligand) CalculateMass() float64 {

// Simplified mass calculation estimation based on atom count

return float64(l.AtomCount) * 12.01 // Assuming Carbon-heavy

}

func (l Ligand) ExtractFeatures() []float64 {

return []float64{float64(len(l.SMILES)), float64(l.AtomCount)}

}

func main() {

// Polymorphic slice of Biomolecules

inputs := []Biomolecule{

Protein{ID: "PROT-AF3-001", Sequence: "MKTVRQER", ResidueCount: 8, AtomicWeights: []float64{110.5, 120.1}},

Ligand{ID: "LIG-DRUG-99", SMILES: "CCO", AtomCount: 9},

}

for _, input := range inputs {

fmt.Printf("Processing %s | Mass: %.2f | Features: %v\n",

input.GetID(), input.CalculateMass(), input.ExtractFeatures())

}

}This code demonstrates the use of Go interfaces to decouple the data type from the processing logic. Whether the input comes from Hugging Face News datasets or proprietary labs, the Biomolecule interface ensures the pipeline remains agnostic to the specific biological entity.

Section 2: High-Concurrency Data Preprocessing

The sheer volume of data required for modern AI is staggering. OpenAI News and Anthropic News frequently discuss the scale of tokens, but in the biological domain, the complexity is geometric. Processing thousands of PDB files to extract angles, distances, and sequences is a CPU-bound task. Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) can be a bottleneck here, which is why data engineering teams often turn to Go.

To prepare data for a model as complex as those discussed in Google DeepMind News, we can utilize Go’s Goroutines and WaitGroups. This allows us to spin up lightweight threads to process files in parallel, maximizing the utilization of multi-core CPUs found in cloud instances like those described in AWS SageMaker News or Azure Machine Learning News.

The following example demonstrates a “Worker Pool” pattern. This is a standard architectural pattern in Go for limiting concurrency (to avoid exhausting memory) while ensuring maximum throughput during the data cleaning phase.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math/rand"

"sync"

"time"

)

// Job represents a single protein structure file to be processed

type Job struct {

FilePath string

ID int

}

// Result represents the processed tensor data ready for the AI model

type Result struct {

JobID int

DataHash string

Err error

}

// worker function processes jobs from the jobs channel and sends results

func worker(id int, jobs <-chan Job, results chan<- Result, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

defer wg.Done()

for j := range jobs {

fmt.Printf("Worker %d started job %d processing file %s\n", id, j.ID, j.FilePath)

// Simulate heavy computation (e.g., parsing PDB, calculating torsion angles)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(500)) * time.Millisecond)

// Logic mimicking data validation found in tools like Great Expectations

// or preprocessing steps for TensorFlow/PyTorch

results <- Result{

JobID: j.ID,

DataHash: fmt.Sprintf("HASH-%d-%s", j.ID, j.FilePath),

Err: nil,

}

}

}

func main() {

const numJobs = 10

const numWorkers = 3 // Limit concurrency to 3 workers

jobs := make(chan Job, numJobs)

results := make(chan Result, numJobs)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Start workers

for w := 1; w <= numWorkers; w++ {

wg.Add(1)

go worker(w, jobs, results, &wg)

}

// Send jobs to the queue

for j := 1; j <= numJobs; j++ {

jobs <- Job{

ID: j,

FilePath: fmt.Sprintf("/data/pdb/structure_%d.pdb", j),

}

}

close(jobs) // Signal that no more jobs will be sent

// Wait for all workers to finish in a separate goroutine

// to allow main to process results simultaneously

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(results)

}()

// Collect results

for res := range results {

if res.Err != nil {

fmt.Printf("Job %d failed: %s\n", res.JobID, res.Err)

} else {

fmt.Printf("Job %d completed. Hash: %s\n", res.JobID, res.DataHash)

}

}

fmt.Println("All biological data preprocessing complete.")

}This pattern is essential when integrating with workflow orchestration tools mentioned in Ray News or Dask News. While Ray handles Python distribution excellently, a Go-based sidecar or preprocessor can reduce the cost of data ingestion significantly before the data ever hits the GPU cluster.

Section 3: Orchestrating Inference Pipelines with Channels

Once data is preprocessed, it must be fed into the inference engine. In the world of Google DeepMind News, latency matters. Whether you are serving a model via Triton Inference Server News or a custom container on RunPod News, the pipeline between the API request and the model execution must be non-blocking.

Go channels provide a primitive for synchronizing data flow without explicit locks. We can design a pipeline where one stage fetches the molecular structure, the next stage tokenizes it (similar to concepts in Hugging Face Transformers News), and the final stage sends it to the prediction endpoint. This is analogous to how LangChain News describes chains, but implemented at a lower, more performant system level.

Below is an implementation of a streaming inference pipeline. It uses the select statement to handle timeouts, a crucial feature when dealing with expensive computations like protein folding which might hang or take too long.

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

// InferenceRequest encapsulates the data needed for prediction

type InferenceRequest struct {

Sequence string

}

// InferenceResponse encapsulates the prediction result

type InferenceResponse struct {

Structure3D string // JSON or PDB format string

}

// generator creates a stream of requests

func generator(ctx context.Context, seqs []string) <-chan InferenceRequest {

out := make(chan InferenceRequest)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for _, seq := range seqs {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case out <- InferenceRequest{Sequence: seq}:

}

}

}()

return out

}

// predictor simulates calling an external AI service (e.g., Vertex AI, AWS SageMaker)

func predictor(ctx context.Context, in <-chan InferenceRequest) <-chan InferenceResponse {

out := make(chan InferenceResponse)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for req := range in {

// Simulate network latency to the Model Server

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case <-time.After(100 * time.Millisecond):

// Mock prediction logic

out <- InferenceResponse{

Structure3D: fmt.Sprintf("PREDICTED_COORDS_FOR_%s", req.Sequence),

}

}

}

}()

return out

}

func main() {

// Context with timeout to ensure the whole pipeline doesn't hang forever

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 2*time.Second)

defer cancel()

sequences := []string{"MKTVRQER", "GGSSGGS", "ALPHAFOLD", "DEEPMIND"}

// Build the pipeline

reqStream := generator(ctx, sequences)

resStream := predictor(ctx, reqStream)

fmt.Println("Starting Inference Pipeline...")

for res := range resStream {

fmt.Println("Received Prediction:", res.Structure3D)

}

// Check if context was cancelled due to timeout

if ctx.Err() == context.DeadlineExceeded {

fmt.Println("Pipeline stopped: Timeout exceeded.")

} else {

fmt.Println("Pipeline finished successfully.")

}

}This pipeline approach allows for backpressure management. If the predictor is slow (perhaps the GPU is saturated), the generator will naturally block, preventing memory overflow. This robustness is key when deploying models discussed in Mistral AI News or Meta AI News into production environments.

Section 4: Best Practices and Optimization in the AI Era

As we integrate the advancements from Google DeepMind News into practical applications, simply writing code is not enough. We must adhere to best practices that ensure observability, reliability, and scalability. The ecosystem is vast, ranging from Weights & Biases News for experiment tracking to Prometheus for metrics.

1. Context Propagation

In the code examples above, we utilized context.Context. This is non-negotiable in modern Go AI services. When a user cancels a request on the frontend (perhaps built with Streamlit News or Gradio News tools), that cancellation must propagate down to the database and the inference server to save compute resources.

2. Integration with Vector Stores

AlphaFold 3 and similar models generate rich structural data. Storing these results often requires vector databases. When using Go drivers for Weaviate News, Qdrant News, or Chroma News, ensure you batch your upserts. Network round-trips are expensive; use buffered channels (as seen in Section 2) to accumulate records before performing a bulk insert.

3. Monitoring and Observability

Unlike traditional web apps, AI pipelines fail silently. A model might return a valid JSON structure that contains garbage predictions. Integration with monitoring tools is vital. While MLflow News covers model metrics, system metrics (latency, goroutine count, channel depth) should be exported. Using Go's middleware pattern to wrap your inference handlers allows you to log every interaction automatically.

4. Hybrid Architectures

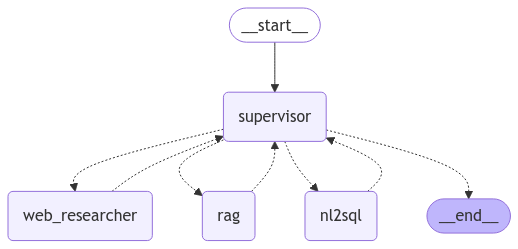

Don't try to do everything in Go. The heavy lifting of matrix multiplication belongs to Python/C++ via TensorFlow News, JAX News, or ONNX News runtimes. Use Go for the orchestration layer—the API gateway, the queue consumer, and the data validator. This "sandwich" architecture (Go -> Python Model -> Go) leverages the best of both worlds.

Conclusion

The recent Google DeepMind News regarding AlphaFold 3 serves as a potent reminder that AI is expanding its reach into the physical world. While the scientific community celebrates the biological implications, the software engineering community must rise to the challenge of building the infrastructure that supports these massive computations.

By leveraging Go’s strong typing, interfaces, and concurrency primitives, engineers can build data pipelines that are not only fast but also resilient and maintainable. Whether you are integrating with LangChain News agents, deploying on Google Colab News environments, or scaling via Kubernetes, the patterns discussed here—worker pools, pipelines, and polymorphic data models—are your building blocks for the future of AI infrastructure.

As we move forward, the convergence of systems programming and machine learning will only deepen. Mastering tools like Go alongside understanding the requirements of models like AlphaFold will be the defining skillset for the next generation of AI engineers.